The avian influenza, or H5N1 bird flu, is a highly contagious viral disease. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that contact with an infected bird or its feces, nasal secretions, or saliva is the main way the virus spreads.

Among birds, the disease is often classified as either Low Pathogenic Avian Influenza (LPAI) or Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI). LPAI has comparatively moderate signs of the disease, while HPAI leads to infections that have a 90-100% mortality rate, with deaths often occurring within 48 hours.

However, bird flu’s range has been expanding to mammalian species. For example, as of March 31, the American Veterinary Medical Association reported that there are 995 confirmed cases of avian influenza among dairy cattle, with a majority of the herds in California, the top milk-producing state in America.

“The more it moves to mammalian populations, the more likely it is to pick up a mutation where it can get into us,” science teacher Mr. Timothy Styer said. “Bird flu has killed thousands of people, but the only way that it has gotten to people has been from direct contact with the animal because it can only infect the two or three proteins in our lungs.”

Styer, who has been intensely following the different variants of bird flu since 2005, confirms that once bird flu, like other avian flues, recognizes the 2/6 receptor, which is everywhere in the respiratory system, then bird flu will be able to be contracted when it gets around the eyes, nose, mouth, and ears.

“That’s the magical mutation they’re waiting for,” Styer said. “Once that 2/6 shift happens, then it will go person to person. Right now, it goes bird or animal to person…the more [bird flu] spends time in the mammalian population, the more it’s liable to pick up that shift, and that’s going to be an issue.”

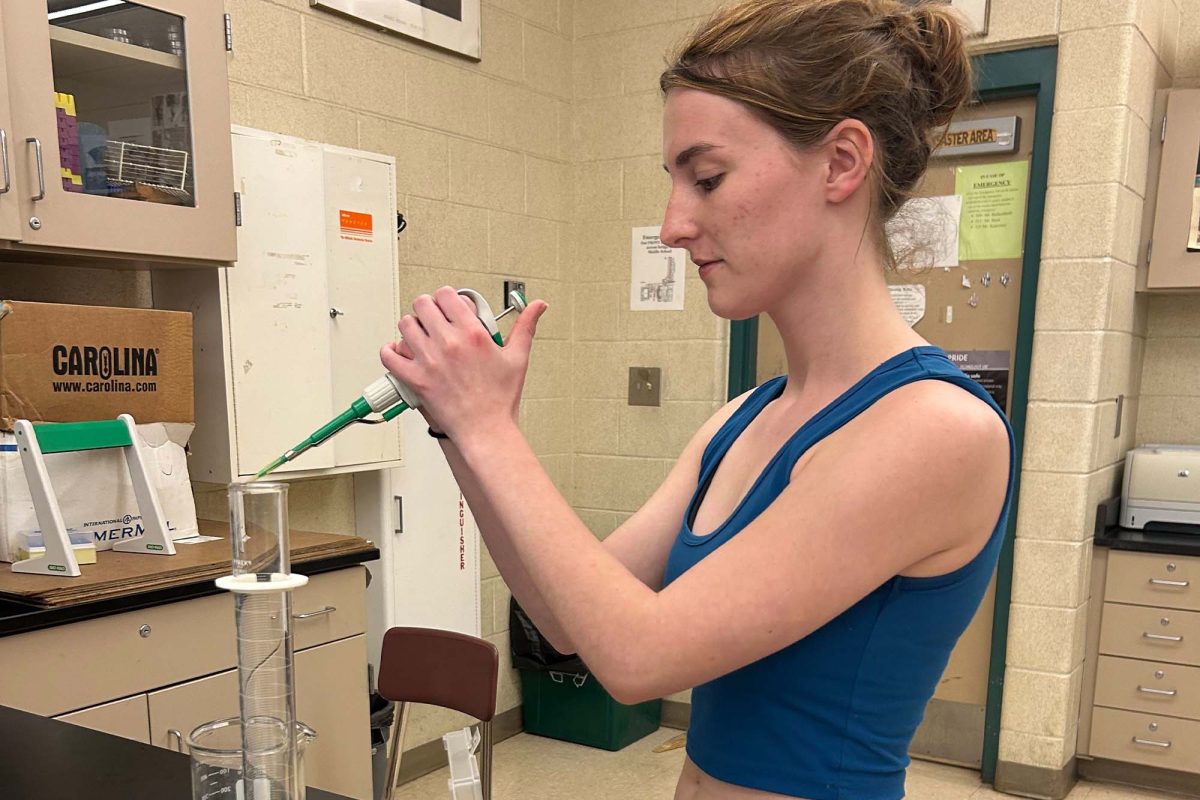

This time right now is critical for detecting cases of the rapidly growing virus and exploring remedies. As reported in the Panther Press in November 2024, researchers were ahead of these discoveries, thus, bird flu posed less of a threat. However, The New York Times reports that the Department of Health and Human Services recently cut $12 billion towards state research on diseases like bird flu, changing the situation.

“We need people out there testing those cows and testing their population, testing to see where it is to follow the variants,” Styer said. “If we don’t, we’re not going to know when that hits the human population…If you cut back funding and you don’t have surveillance and you don’t have the ability to test, and you don’t know where they are in the variant, we’re going to be unable to know when this shift happens.”

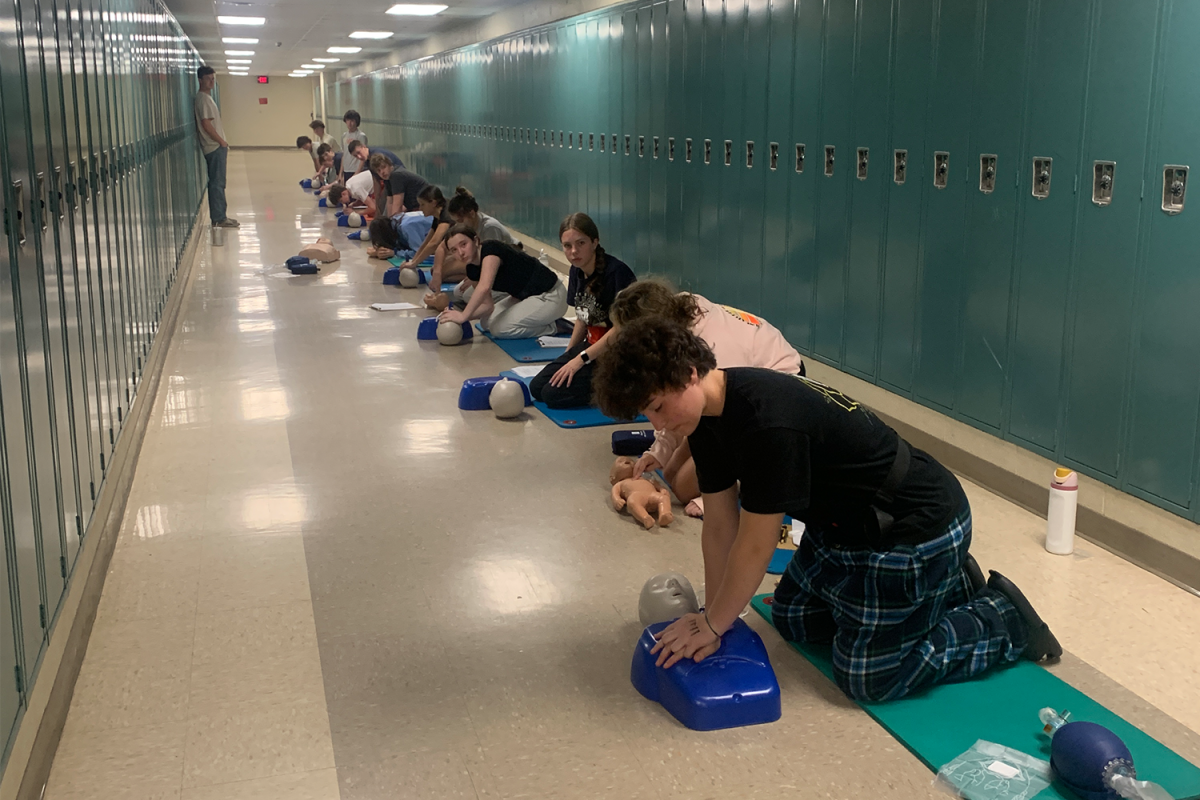

Although treatment against type A flus exists, too much confidence is placed on these remedies. Without a close eye on this rapidly mutating disease, Styer confirms more people will be harmed than need be. For students, the funding cuts’ effect on bird flu studies foreshadow concerns about the future of research.

“I have friends who want to do research in the future, so the fact that many labs don’t have the funding to do that right now is scary,” sophomore Ming Cerdan said.

However, some students take this as an opportunity to independently seek information and increase their awareness of health-related news.

“I know that the government is concealing a lot of stuff about viruses, like bird flu, going around. I signed up for World Health Organization (WHO) email reports so I can see if there are outbreaks in the US or near here,” sophomore Maddie Schimpf said.

Although one can never predict when exactly bird flu will mutate to allow human-to-human transmission, it is important to stay updated on information about bird flu, given its rapid spread and effect.

“So, is it tomorrow? Will it be next week? Will it be a month, will it be a year? I’ve been here now since 2005, but I’m hearing more and more about bird flu recently, and the more you hear about the additional infected populations, the scarier it is,” Styer said.