For as long as I could remember, Sundays were spent in Chinatown. Here were merchants selling sprouts of uncommon vegetables to my mother, who would plant gourds and greens from her homeland. Here was the sound of friendly bartering and fish splashing from large tanks to be taken home in plastic bags. The smell of fried dough and luxurious red bean buns drifted, coating my lungs. For me, Chinatown is a second home.

Offering an intersection between diverse identities within a major American city, Philadelphia’s Chinatown provides a sense of belonging for many Asian Americans, including senior Michelle Ding.

“[Chinatown is] a way for a lot of Chinese Americans and people who might be further removed from their ancestry to feel connected to a part of themselves that they really don’t see represented in a lot of other places,” Ding said.

This valuable community is threatened by the proposed $1.5 billion Sixers arena (called 76 Place) to be built on Market Street between 10th and 11th streets, bordering the entrance to Chinatown. Construction of the arena is scheduled to begin in 2026, opening for its first basketball game after the expiration of its current lease in 2031 at the Wells Fargo Center.

“I feel like the fact that we’re considering building an arena over what is one of the few dedicated cultural safe spaces for East Asians in Philadelphia is crazy,” Ding said. “I understand that cities run on money… But this is one of the very few places where people who have immigrated to America, specifically to Philadelphia, can find a sense of home away from home.”

My dad came to America in the 1990s to pursue a Ph.D., and my mom followed soon after to complete her master’s degree. They arrived with only a suitcase and a visa, tongues adjusting to the unfamiliar consonants of English.

Veelo Liang, a Taiwanese-American and parent of senior Joe Hsu, has been in the United States for 37 years and has been involved in Chinatown since her arrival.

“I feel like when I came here, it was very nice that I was surrounded by a lot of the people in Chinatown… I can hang out with people of [a] similar background and then we can have a common language,” Liang said. “When I say common language, [it’s] not just the Chinese language. I’m talking about cultural ideas.”

Senior Cherlin Tjio is concerned that the arena will disrupt Chinatown’s function entirely.

“If this project goes through, the way that we access Asian groceries, Asian food—the ease of access—would be lost because, obviously, the 76ers arena traffic would take over everything,” Tjio said. “Not only that, the rent for local businesses who are trying to make a profit would go up and the people living there would also have to pay more to live there…it would just ruin the point of having an easy place to connect with other Asian people.”

The 76 Place forces community members out and increases traffic, limiting access to essential services such as visa applications and other community support initiatives for Asian immigrants.

Language is often a barrier for non-native English speakers to receive necessary care; Liang spent over 20 years volunteering at Holy Redeemer Chinese Church in Chinatown to help those with this challenge.

“Regular people sometimes don’t know how to see a doctor, but think about a person [that doesn’t] even speak English, right?” Liang asked. “I would go to the clinic with them and help them translate.”

She explains the important role community members, such as the priest at Holy Redeemer—a former lawyer—had in helping new immigrants adjust to life in America.

“Chinatown is important to provide this kind of [service] because then you have a lot of Chinese people there [who] at least speak the language…That’s the part of Chinatown [that] I know the most,” Liang said.

Philadelphia holds one of the last authentic Chinatowns; the Asian community and businesses that brought DC Chinatown to life didn’t survive after the construction of the Capital One Arena in Washington DC, in 1997.

To avoid this, the City Planning Commission is doing an impact study, which has yet to be released as of April. The full breadth of the economic and community impact of the arena can not truly be understood until its release, which has been delayed for over three months.

Save Chinatown, a movement to preserve the 150-year-old community, has faced multiple harmful project proposals in the past. They successfully fended off plans to build a federal prison, casino, and a Phillies stadium, but they haven’t always won. In 1991, the Vine Street Expressway divided Chinatown into two parts. Now, the Sixers arena threatens to end the community altogether.

Class of 2020 Strath Haven alumni Cindy Zhang is a part of Asian Americans United, which works in tandem with Students for the Preservation of Chinatown to involve young people in Philadelphia in the Save Chinatown movement—inspiring Strath Haven’s Asian Haven Club to take action too.

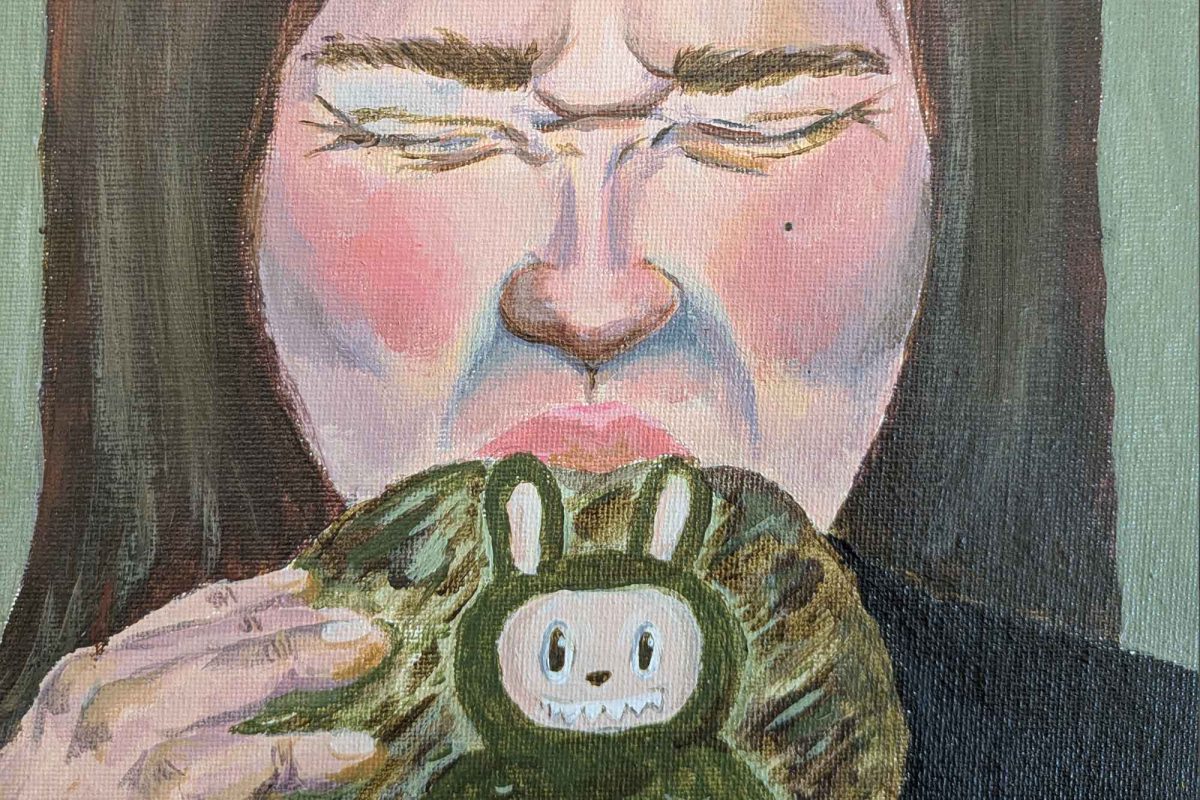

Zhang highlights a recent project entitled “Our Chinatown” that showcases the many voices of Philadelphia’s Chinatown.

As Zhang described, the project comprises large red posterboards containing Chinatown community members who explain what Chinatown means to them.

“We have people who have grown up in Chinatown their whole lives, local business owners, and community members. A very, very large majority are opposed to the arena, and they acknowledge and understand the impact on its people, its businesses, and homes, families, schools, everything,” Zhang said.

Each person’s story is displayed around Chinatown and found online.

Chinatown is a home. It’s where a community worships, celebrates traditions, and buys groceries. I can’t imagine a life without this connection to my Chinese identity.

“Ways to find revenue are necessary for the city,” Ding said. “But that should not come at the expense of people’s entire lives and their connection to culture.”

This year’s International Day event on April 15 and school assembly on April 19 highlighted the Asian Americans United and the Save Chinatown initiative, supported by the Strath Haven Asian Haven Club.